“I started writing full time in 1999 and often saw my articles being published in some newspapers, which I didn’t submit articles to nor did I receive any payment from. Sometimes I sent letters or made phone calls to them demanding remuneration, but was required to produce evidence that I was the author of the said articles and show my ID card, which was very troublesome. I was very angry. This phenomenon became increasingly common later on. So, I consulted one of my lawyer friends, who told me that the Copyright Law allowed newspapers to use a published work without permission from the copyright owner and the remuneration thereof was paid at 50 Yuan per thousand words (the tariffs of payment for reproducing articles). Failure to pay the author on the part of the newspaper violated the author’s right to remuneration. If requesting remuneration through a lawyer, I can only demand two to five times of the 50 Yuan per thousand words, which was not enough for the lawyer’s fee. Therefore, I gave up,” said Lin Xi, a female writer from Dalian, feeling indignant and helpless when finding that her articles were used at will without notification.

From “struggling for honor” to “making money”

Lin Xi’s first action to enforce her legal rights began in July 2002. A southern best-selling documentary magazine used 9 of her works in its fine compiled edition. However, the magazine did not contact Lin Xi before the use nor did it pay remuneration to Lin Xi after the use. Lin Xi was a signed author of this magazine and wrote documentary articles for it. The tariff of remuneration was 1,000 Yuan per thousand words. Yet, she failed when demanding remuneration for the 9 articles. So she consulted a lawyer. The lawyer told her that the magazine’s conduct infringed her copyright and the amount of compensation for the infringement may be calculated by referring to: i) the author’s actual loss; ii) the infringer’s gains from infringement; iii) and the judicial ruling of no more than 500,000 Yuan based on the circumstances of infringement. As a result of the difficulties of calculating Lin’s actual loss, Lin’s lawyer decided to calculate the amount of compensation by referring to the profits the infringer gained from the infringement, i.e., first calculating the gains of each issue of the magazine based on its circulation and pricing published by the magazine’s website, then calculating the gains from the infringement according to the ratio of infringing articles to the entire articles. After calculation, the final amount of compensation was 90,000 Yuan, including economic loss, notarial fees and mental anguish. After more than a half-year’s trial, on January 14, 2003, the Xigang District People’s Court in Dalian ruled that the magazine compensate Lin 24,000 Yuan for various losses and pay the legal fees of 1,100 Yuan. Dissatisfied, the magazine appealed to the Dalian Intermediate People’s Court. In the second instance court session, both parties reached a settlement. The magazine paid Lin 21,000 Yuan in compensation.

Lin Xi said that her rights protection action went smoothly, though it took half a year. Some friends were concerned about her and

dissuaded her from offending magazines and newspapers, fearing that it may affect the development of her career. After all, authors and newspapers are interdependent. Though a little wavered, Lin was determined to resort to law. Lin Xi said that she was a person who lived by writing and the free use of her painstaking effort not only violated her dignity but also threatened her survival. Nonetheless, the magazine did not make things difficult for Lin Xi after the lawsuit and it expressed that its main business was to publish original documentary articles rather than reproduce those published articles. It still maintained a cooperative relationship with her afterwards. This relatively satisfactory result strengthened Lin Xi’s confidence in safeguarding her legal rights. “At first I just want to struggle for honor. Why use my articles casually without showing respect for my work. I didn’t expect that it could make money,” said Lin Xi.

Targeting at professionalization of rights protection

Following the above experience, Lin Xi made a more rational and detailed plan to defend her legal rights. In view of the difficulties of evidence collection arising from the only local-based distribution of some newspapers as well as the high cost of rights protection resulting from the low amount of compensation, Lin Xi finally decided to target the books published by the publishing companies. That decision was also triggered by an accidental finding. Once she browsed through a bookstore and found that some books used her articles that she had been unaware of previously. Lin summarized that there were many compilation books in the current book market, and this type of book was in need of a large number of articles with many authors being involved, most of which violated the rights of the copyright owners. Some of them directly used the authors’ original text with the authors’ appearing, which was better as it only violated the author’s right to compilation and remuneration. Some cases are serious because the infringers made only superficial changes to an author’s article and then used it without affixing the author’s name, which not only violated the author’s right to remuneration, but also the author’s right of modification. Under the Copyright Law, no person shall modify an author’s works without permission from the author. However, currently most of the copyright owners failed to hold these copyright violators liable for their conduct.

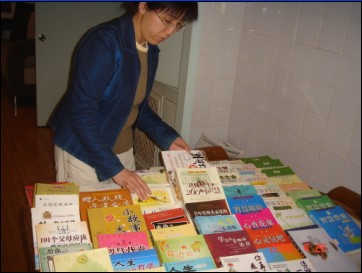

If an author cannot receive the income due to him or her under law, he or she is entitled to ex postfacto compensation under the law. Lin said: “As a rule, if paid normally, the tariff of remuneration of a publishing house is 50 Yuan per thousand words. However, if the court is involved, there will be compensation, which is generally 5 or 6 times of the normal pay. That depends on a region’s economic level. Once after the conclusion of a lawsuit the other party’s lawyer from Guangdong came to me, telling me privately with a smile that 3,000 Yuan for one article, the amount I demanded, was low, and in their region the compensation for one article was at least 10,000 Yuan. Therefore, assistance from a professional lawyer is a must during the process of safeguarding one’s legal rights. However, lawyers are unwilling to take this type of copyright case because they gain little from it in comparison with other types of cases. Thus, one may retain a lawyer in a small law firm to handle such cases. My lawyer and I have a clear division of labor. I am responsible for collecting evidence because I know which works of mine were infringed, and the other aspects are left to the lawyer to handle. Costs for rights protection mainly include legal fees, cost for purchasing infringing books, charges for express deliveries, and expenditures for sending letters and making phone calls to the other party. The income from rights protection is divided between my lawyer and me, with 20% going to the lawyer. So rights protection is no longer just my personal thing. Sometimes in a lawsuit, my friends may intercede with me for the other party, to which I felt helpless because compensation concerns not just me but also the lawyer.” After the arrangement of these basic necessities, Lin began her eight-year-long professional rights protection. Lin said, “Though I earned an income through rights protection, I’m a full time writer after all and cannot devote all my energy and time to defending my rights. I need time to continue my writing. I usually defend my rights every half a year or every quarter, spending about one week going to the book markets in Dalian to make a thorough search. Generally, as long as it is a compiled-type of essay collection or inspirational book, it may use my articles. I also conducted such searches occasionally on the Internet. I entered the titles of my articles and searched, and then some books appeared. Until now, I have bought 200 infringing books containing 300 articles of mine. Later I expanded my search area. I found my articles in teaching assistant books as well as books on business plans. I filed lawsuits in batches, targeting 10 to 20 infringing objects each time.

The memory of rights protection

According to Lin Xi, there have been nearly 100 publishing houses infringing her rights from the commencement of her defense of her lawful rights in 2002 to the present. Generally, before initiating a lawsuit, her lawyer would send a letter to the infringing party first. Most publishing houses showed a positive attitude after receiving the lawyer’s letter. They responded with apologies and negotiated for settlement. 60% of them reached an agreement with Lin after negotiation. Some even established a long-term cooperative relationship with Lin because of this event. However, some publishing houses dragged their feet and failed to make any effort to remedy the situation by the deadline. Thus, the lawyer would file a lawsuit. Ultimately, many of the publishing houses shifted favorably after receiving the complaint. 80% of the cases were settled prior to court. The amount of compensation obtained through settlement would be higher than that via the lawyer’s letter due to the increased cost of litigation. Only less than 20% of the cases went to trial. Overall, the entire process of rights protection went well with only occasional twists and turns.

In terms of time, the shortest case was the one filed against the Nanfang Press in 2006. It published a series of essay books, which contained over 10 articles by Lin. Lin’s lawyer sent a letter to the publisher and there was no response. So Lin brought the case before the court. The case was settled half a month after it was entertained and the opposing party’s attitude was very good.

The longest case is the one against Dalian North Pearl Television Production Communications Limited (“North Pearl”) in November 2008. In July 2008, Lin Xi entered into a contract with North Pearl regarding the creation of the teleplay Paper Wedding Year. North Pearl only paid Lin part of the remuneration and the balance remained unpaid. After many unsuccessful negotiations, Lin delegated Mr. Xiang Kunlun, a lawyer from the Liaoning Fada Law Office, to initiate legal proceedings. Prior to the legal proceedings, Mr. Xiang went to the Xigang District People’s Court in Dalian for consultation. The court held that it was a contract dispute and should be adjudicated in the district court. They formally accepted the case. In December 2008, the court tried the case, rendering a judgment in favor of Lin, requesting North Pearl to pay Lin the balance of 60,000 Yuan as well as 20,000 Yuan for breach of contract. Dissatisfied, the defendant appealed to the Dalian Intermediate People’s Court, that ruled it as a copyright dispute, over which the district court had no jurisdiction, and the district court’s judgment was therefore invalid and the case should be removed to the intermediate court. However, during the process of removing the case files, a new law was promulgated. Under the new law, this case should be tried first in the district court. Thus, the originally simple case became complicated. The case files needed to be removed from the Xigang District People’s Court to the Dalian Intermediate People’s Court and then be returned by the Intermediate People’s Court to the District People’s Court for retrial. It has been over a year. The case is still in the process of being removed and to date there has been no litigation.

Making profits from the loophole of copyright

Over these years, Lin Xi has recovered more than 200,000 Yuan in copyright damages through rights protection. It can be seen from this that there exists a great copyright loophole due to the weak copyright awareness among the Chinese copyright owners. Most often the infringers have a fluky psychology that once being found, they can send the authors away by paying some remuneration, and if not, the remuneration will be saved. They are unaware of the fact that if a copyright owner deliberately enforces his or her rights, they will suffer greater losses, which is called by some media the “fishing method of rights protection.” So what makes the fish bite?

Getty Images China (“GIC”) is a large company in terms of safeguarding copyrights. According to an insider, GIC distributed images through the network. Many people took chances by using GIC’s published images freely and without the knowledge that all they were under supervision and control. It is as if you are walking along a street and find a wad of cash lying on the ground. You think that nobody notices you, but actually many eyes are staring at you. GIC will not look for clients themselves most of the time. It has its own veteran team of lawyers, responsible for carrying out searches in various places such as exhibitions, color pages of advertisements and outdoor advertising. GIC’s targets include various advertising companies and wealthy business owners. In recent years, due to the popularity of the networks, a substantial number of enterprises chose to build their own websites. The random use of photos and pictures on websites is far greater than that of billboards. Naturally, these websites are included in the search.

According to incomplete statistics, over 5,000 companies were sued for “infringement” by GIC in 2006. The number has steadily grown from 2007 to the present, covering state-owned enterprises, private enterprises, institutions, non-governmental organizations and even government agencies. With solid evidence in hand, GIC prevailed at most local courts around the country. The courts have ruled that the defendants pay damages for each “infringed” image, ranging from 5,000 Yuan to 10,000 Yuan. The plaintiff’s expenses incurred from safeguarding its rights such as retainer fees were undertaken by the defendants. If a company can run its business through rights protection lawsuits, it indicates the weakness of people’s copyright awareness and hugeness of the copyright loophole, which is startling.

Patching the hole

Copyright Law was not implemented until 1991. Compared with several hundred years of protection in the west, it is inevitable that there exists a substantial gap in the awareness of IP protection. However, with China’s entry into the WTO, IP issues have become significant and cannot be avoided. Many authors held the view that punitive damages against the infringers were too low, which would result in the high cost of enforcing their legal rights. They had no option but to waive their rights. These problems will be solved with China’s vast attention on IP protection and the accumulation of legal practice in IP protection.

The emergence of rights protectors and the fishing method of rights protection enable people to realize the sanctity of intellectual property rights. However, the problem cannot be solved overnight. A known publishing house expressed, “We felt very helpless when some authors came to us to enforce their legal rights. Copyright issue is an issue we have attached great importance to. For example, we constantly strengthen our editorial management, hoping to control infringement from its source. We often remind our editors to be clear of the sources of the manuscripts. But in specific operations it is still hard to accurately verify the originality of each article. For this reason, we have laid down some rules in this respect. For example, in an effort to avoid the risk of copyright litigation, the editors, in selecting subjects, signing contracts, reading and processing articles for the purpose of non-original books, should raise their legal awareness regarding copyright and consciously avoid and prevent the occurrence of IPR infringement. Meanwhile, to fundamentally avoid cases of IPR infringement, we temporarily ceased our cooperation with small cultural companies, refusing to accept non-original topics. In the event that disputes arise regarding such matters as copyright, the editor concerned shall take full responsibility and be punished in accordance with the relevant rules.” IP