With the intensification of economic globalization and the development of the network technology in the digital age, communication tools as well as related digital technology products have captured a wide range of audiences around the world. Against this backdrop, the industrial design protection of graphical user interface (GUI) of electronic products has become a new trend in recent years. Countries and regions whose IT industries are relatively advanced, such as the United States, the European Union, Japan and South Korea, have all set up industrial design protection systems of GUIs successively whether through separate legislations, or by re-elaborating the original patent laws. Whether legal protection requires substantive examinations or only formal examinations for the applications to be granted, the protection scope of GUIs has gradually been extended from static computer-generated icons to dynamic animated patterns.

China’s Patent Law has not yet defined a GUI or stated the legal protections of a GUI in electronic products. However, in practice some departments have realized the significance of this matter. But, in the 2006 edition of the Guidelines for Patent Examination (Guidelines), an intermittent pattern shown when the product is electrified is explicitly excluded from the protection of industrial design. The 2010 edition follows suit of the 2006 Guidelines, which is contrary to the international trend. This article therefore highlights the IP protecting issues concerning GUIs in the United States, the European Union, Japan and South Korea.

The United States

The protection of GUIs in the United States is mainly conducted through the patent law. Different from China, the United States requires substantive examinations in design patents. It also allows the same subject matter to be eligible under various possible overlapping IP protections. Protection of design patents is provided in Articles 171, 172 and 173 under Chapter 16 of the current U.S. patent laws.

The history of protecting a GUI as design patent dates back to the mid 1980s, the system was created in response to the needs of enterprises. At that time, Xerox filed design patent applications for several computer software icons and protection was granted. Fig. 1 below is one example. It depicts the design patent application of an icon of a telephone whose patent number is D295764.

Fig. 1

The new protection mode aroused wide attention of the U.S. patent agents and attorneys, but the process was not smooth. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) quickly received feedbacks and advices. Although the majority expressed their supports on this move, some people thought protecting computer-generated icons as design patent eroded the protecting scope of the traditional copyright law. On this ground, the USPTO began to reject such applications. In 1989, the Director of the USPTO stated clearly that since software icons did not belong to the subject matter scope of design patents, they ought not to be patented. Thereafter, several applications of Xerox’s were rejected, which included an application (No.07/303608) for an icon embedded in a screen display which was filed on January 26th, 1989. Xerox applied for reexamination. After hearing the case in January 1922, the Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences made the famous Ex parte Strijland decision in April which exerted profound influence on the protection of GUI in the U.S.

In the Ex parte Strijland decision, the Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences held that the applications of the Xerox failed to point out specific industrial products, thus did not satisfy 35 U.S.C. 171’s requirements. Meanwhile, since the claims were not clearly enough, the application also failed to meet the requirements of the 35 U.S.C. 112. In other words, the significance of this decision lay in that the USPTO indeed admitted that an icon embedded in computer screen display was patentable as an inseparable part of the computer hardware as long as it was accurately described. Therefore, it could be protected as design patent.

Since then, the attitude of the USPTO towards the design patent applications of computer-generated icons changed. In the second revision of the USPTO’s Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) released in July 1996, a separate section of “Guidelines for Examination of Design Patent Applications Claiming Computer- Generated Icons” was included. The end of the section also stated that similar applications whose patent right had not been ascertained before April 1996 should be examined according to the new guidelines. Although the material on “computer-generated icons” was not an entirely identical concept with “user interface,” the former was the basic component of the latter. If “icons” are eligible for design patent protection, it means that the door has been opened to the protection of user interface.

In addition, a decade after the MPEP stated explicitly that static icons embedded in screen displays could be protected, the USPTO once again confirmed in the MPEP that dynamic patterns should also be subjected to the protection of design patent. Fig. 2 is an example of a design patent application whose grant number is D530339. It is a dynamic pattern showing that there is a phone call.

Fig. 2

The current MPEP gives specific guidelines to the examination of design patent applications concerning computer-generated icons. Firstly, it listed the general examine principles of whether the application complies with the 35 U.S.C. 171’s provision for “a design for an article of manufacture.” According to the prior decision of U.S. Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences, “pure computer-generated icons are merely flat-decorations.” But computer-generated icons embedded in articles of manufacture are subject matters under the 35 U.S.C. 171’s provision. Therefore, if the applied computer-generated icon is embedded in computer screen, screen display or other displays or part of the aforesaid screens or displays, it can be deemed as satisfying the requirements of the 35 U.S.C. 171. That is because a design patent must be inseparable with the article of manufacture it applies to and can not exist as an independent flat-decoration.

In July 2006, MPEP incorporated “changeable computer-generated icons.” This gave a green light to providing design patent protection to dynamic computer-generated icons which may appearance change during operation or allows observation to indicate the stages of progress of the underling application. Customers could forseeably expect if not demand icons which not served only showed deviations on an icon to indicate to display varying medical stages of testing degree of level or progress and patent holders were not required to maintain a consistent an static image to consumers to be protected. Applications falling into this class are allowed to demonstrate a range of evolving images that corresponded to their function may be protected so long as the views are ranked in accordance with the display order, and possessed no ornamental characteristics subject to change.

Experts pointed out that the USPTO might have been motivated to provide legal support and protection for icons that underwent transitional changes filed by enterprises such as Verizon and Microsoft. In fact, since the change has been made, these companies have been the most active applicants. According to statistics by the end of 2009, more than 70 of the granted 100 (approximately) design patents of changeable computer-generated icons comes from Microsoft. It could be said that the design patent protection of GUI in the U.S. meets the needs of enterprises. The practical issue facing the U.S. is that since industrial design is protected under the patent law and the grant criteria of design patent is the same with patent; it is confusing whether the protection of GUI emphasizes on aesthetic features or on functions connected with techniques.

The EU

To enable the free flow of people and goods between EU members, the EU has been trying to unify IP legislations. In 1998, the EU released “Directive 98/71/ EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13th October 1998 on the legal protection of designs” (Directive 98/71/EC). In 2001, it issued the “Council Regulation (EC) No. 6/2002 of 12th December 2001 on Community designs” (Council Regulation (EC) No. 6/2002). The latter create the “Community design right,” and incorporated the concepts of “Unregistered Community Design” (UCD) and “Registered Community Design” (RCD). According to it, a single application for Community design enables the subject matter to be protected and enjoy the same rights in all EU member countries.

Council Regulation (EC) No. 6/2002 defines “design” and “product” explicitly. Article 3 (a) provides that “design” means the appearance of the whole or a part of a product resulting from the features of, in particular, the lines, contours, colors, shape texture and/or material of the product itself and/or its ornamentation.

Article 3 (b) defines that “product” means any industrial or handicraft item, including inter alia parts intended to be assembled into a complex product, package, get-up, graphical symbols and typographic typefaces, but excluding computer program.

From the definition mentioned above, it can be seen that in design patent protection, EU protects the “design” rather than the “product” itself. Meanwhile, graphical symbols are explicitly included in the protection scope of product, which provides legislation support for GUIs to qualify for design protection.

Council Regulation (EC) No. 6/2002 also stipulates that only when design possesses novelty and individual character can be subjected to protection. According to Article 5, “a design shall be considered to be new if no identical design has been made available to the public.” Article 6 provides that “a design shall be considered to have individual character if the overall impression it produces on the informer user differs from the overall impression produced on such a user by any design which has been made available to the public.”

Although both the Directive 98/71/EC and the Council Regulation (EC) No. 6/2002 give a clear definition to “product” and point out specific product types which are excluded from protection, they do not extend the protection scope from designs to products. That is to say, when examining a design application, the key issue concerned is the design itself rather than the product it applies to. Article 19 of the Council Regulation (EC) No. 6/2002 provides that “a registered Community design shall confer on its holder the exclusive right to use it and to prevent any third party not having his consent from using it.”

However, the concept of “product” does have an impact on individual characters. When judging the “overall impression,” despite the free play of the designer’s creativity, the nature of the product and the category the product falls into should also be considered. Meanwhile, the Examination Guidelines for Community Design clarifies that “the application must further contain an indication of the products in which the design is intended to be incorporated or to which it is intended to be applied.” However, it also states that: “the examiner has to bear in mind that the classification of products serves exclusively administrative purposes. It does not affect as such the scope of protection of a Community design.”

The most prominent advantages of the protection system of Community designs are that they are protected by separate legislation and do not need not to undergo substantive examinations. However, though the scope of product is quite wide, computer programs are still excluded from protection. The intention of the exclusion has triggered controversies. If it is only because of the already existing Directive 2009/24/ EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23rd April 2009 on the legal protection of computer programs and the intention of avoiding overlapping protections, the current legislation is clearly not simplified enough and likely to cause ambiguities.

Japan

In Japan, designs are protected under the Design Law, which is independent from Japan’s Patent Law and adopts substantive examinations. To date, it has become the core of the protection system for designs in Japan. In Japan, the protection for GUI completely results from country protection to the electronic industry. Since the 1980s, Japan’s semiconductor industry has assumed a leading position in the global market. With the popularization of home appliance products with LCDs, the Japan Patent Office (JPO) revised the Design Examination Guidelines to begin providing protection of parts displayed on the liquid crystal panel, but the protection is limited to certain conditions. In 1998, Japan revised its Design Law to start protection of partial designs which enabled protection of only the liquid crystal display part as a partial design. The electronic watch and mobile interface can all be protected by the Design Law.

According to the explanation of the JPO, to pass the examination and get design protection, a “graphic display design” must concurrently satisfy three conditions. The JPO outlined what factors examiners consider and provided examples applicants seeking protection as follows:

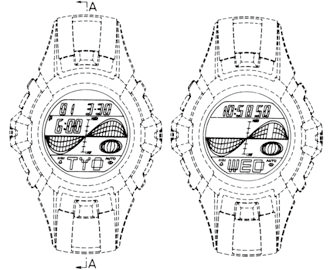

(1) What the design shows must be indispensable for the product to achieve its functions. This requires a direct link between the design and product functions. Take the watch in Fig. 3 for example; the time and date displayed must be indispensable content to achieve its functions. This is also true to Fig. 4 in which the content displayed on the control panel of the mobile phone is also indispensable to achieve its functions.

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

(2) The design must be displayed by the display function of the product itself. If the interface design is displayed through an external display device, it cannot be protected. Thus, GUIs of devices relying on external display such as VCR, DVD player and other devices are excluded from protection.

(3) When there is a change in the design view, the change must follow a particular and consistent course predefined by a law. This will presumably be determined by software or circuitry within the device in response to external input or factors. For example, the applicant described the changes of the content displayed by the mobile phone as “displaying the tidal level, change in the time and days of a week.”

These three conditions narrow the protection scope of the GUIs greatly. In fact, JPO summarized the GUIs which could receive protection in the past as: “designs of the initial menu which are displayed by the product itself and bear close relationship with the functions of the product.” The scope was quite narrow.

In the first decades of the 21st century, the Japanese government conducted many forums on whether GUIs should be included within the protection of the scope of design. After two large seminars held successively in 2001 and 2003, the Institute of Intellectual Property concluded that the Design Law should be amended appropriately to incorporate graphic images in the protection scope. On July 3rd 2002, the “IP Strategy Outline” was released on the “IP Strategy Conference” which brought the aforesaid amendment into the agenda and declared a fundamental policy to “strengthen protection for designs.” In the “Strategy Conference of Applying Designs Flexibly” held by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry of Japan (METI) in 2003, adding graphic designs into the protection scope of the Design Law was proposed once again. Under the leadership of METI, the “Small Committee of the Design System” organized 10 meetings to discuss the details of the amendment before they at last came up with the report of “the idea status of the design system” and put forward concrete proposals for the amendment. Their proposals included redefining the subject matters of the design protection and introduce GUIs to the protection scope of the Design Law.

Eventually the proposals were accepted by the legislation department. In 2006, the Design Law was revised to commence protection of graphic images for operating articles.

As provided in the latest edition of the Examination Guidelines, a design falls within the scope of protection only if it satisfies the following conditions:

1) The product in which the GUI is applied to must comply with the definition of “product” according to Japan’s Design Law. The GUI displayed on a product must be indispensable for the product to achieve its functions.

2) The graphic must be reserved in advance of the manufacturing of the product. Any graphic which is reserved in external memory medium or copied into the product after it has been manufactured is excluded from protection.

3) The graphic must operate concurrently with the product, which includes being viewed by the display function of the product itself and being displayed through a display device which is under unified use with the product. The scope of the former remains the same as the protection standards which have been in place since the 1980s, while the latter extends the scope to products which rely on external display devices, such as DVD players. However, the subject matter is still limited to components able to assist the functioning of the product. For example:

Fig. 5

From the above it can be seen that compared with the U.S. and the EU, Japan is rather strict on protecting GUIs and not all GUIs are subject matters which fall under the protection scope of the Design Law. This is closely related to its industrial strategy.

South Korea

South Korea also protects designs through separate legislation. In the 1990s, the electronic industry of South Korea grew by leaps and bounds, and acquired independent R&D ability bit by bit. In order to maintain the technical advantages it had already gained in the electronic communication related industries, South Korea started to strengthen its IP protection through various measures, such as amending the Industrial Design Protection Act in 2003, to protect visual designs, including GUIs.

The scope of protection for visual design includes:

1. GUIs, for example:

(1) Website GUIs of the web page of the Korean Intellectual Property Office and the web page of Incheon International Airport, etc.

(2) GUIs of application software such as Microsoft Word input software, Windows Media Player, etc.

(3) Mobile GUIs, such as the GUIs embedded in mobile phones, PDAs and Web Pads.

2. Icons

(1) Application Icons such as the IE Icons.

(2) Icons used individually or as a set of tools.

(3) Icons as components of GUIs.

(4) Graphic Images such as graphic designs for characters, computer screen protectors, characters, 3D animations and displays stating the status of various functions, etc.

Examination of such designs requires that the GUI must be embedded on an actual article. It does not matter whether it is embedded on the whole article or just on a part of the article. It should be related to the functioning of the article. In addition, moving designs could also be protected in South Korea. Clearly, the protection scope for GUI in South Korea is much wider than that in Japan while its protection for designs of portal pages is rarely seen in other parts of the world.

South Korea protects visual designs because it recognized the importance of visual designs in the digital era. The South Korea government thinks that firstly, visual designs speed up information transmission. Visual designs serve to display the operation menu and operating status of a multifunctional article, as well as transmit large amounts of information to users in limited space for efficiency of use.

Secondly, visual designs simplify operational approaches. A GUI is one of the best examples of this approach. These designs simplify the use of orders and programs from text input to icon selections.

Thirdly, increase the aesthetic height of displayed images. The designs satisfy the aesthetic senses of consumers. They represent the subjective aesthetic consciousness of the designers and unique characters of the products.

The protection for GUI in South Korea is more purely motivated by industrial interests. The protection mode is not focused exclusively on accelerating the development of the industry through legislation. It is the result of consolidating the advantages with legal frameworks after the industry had gained a leading position globally and sought further governmental supports. This approach has yielded conspicuous results in South Korea. South Korea enterprises such as Samsung and LG gradually have gained increasing market shares in the global market and have become reputed names around the world. The rise of South Korea enterprises began to worry their American rivals. Apple and Samsung’s disputes over the designs of smart phones are among the best examples of how worried American enterprises may attempt to retain their market restrain the rise and expansion of competing enterprises.

(Translated by Monica Zhang)

|

Copyright © 2003-2018 China Intellectual Property Magazine,All rights Reserved . www.chinaipmagazine.com 京ICP备09051062号 |

|

|