Electronic devices , led by mobile phones, tablets and computers, have become an essential part of our lives. Most present-day electronic devices feature user-friendly human machine interaction experience made possible by the introduction of graphical user interface (GUI), which uses graphical elements like windows, icons and menus to carry out commands and thus allows for a simple and natural interaction between users and electronic devices. Things were very different in the age of command-line interface (CLI ) , the text-based user interface that required users to memorize and type in individual commands. GUI resulted in the phasing-out of CLI and eventually became, and remains, the mainstream.

The proliferation of GUI - based electronic devices has resulted in an increase in the business value of GUIs. This has spurred many tech companies (especially software developers) to seek protection for their GUI designs in China using the patent system (as designs are protected as design patents in China), the copyright system, or both. This article primarily examines t h e design patent approach in China following a landmark case recently decided by the Beijing IP Court.

1.Patent legal framework for the protection of GUI designs

The 2010 Patent Examination Guidelines issued by the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) states that patterns shown when the product is powered on (such as patterns on an electronic watch dial, patterns on the screen of a mobile phone, software interface) are ineligible for design patent protection.

There is no question that such patterns per se are not patentable. Nevertheless , some debate arose over the issue of whether products that incorporate such patterns (i.e. GUIs) are patentable in their entirety. Design patent applications for such products had usually been rejected until a 2014 decision of the Beijing Higher Court, Patent Reexamination Board of CNIPA v Apple Inc. [Case No.(2014) High Court Administrative (IP) Final No. 2815] changed that approach. In this case, the Court overturned a decision of the Patent Reexamination Board and decided that, even though a product incorporates GUIs, the product in its entirety should be patentable because the GUIs are only part of that product.

Later in 2014 the CNIPA then made a few small, but significant, changes to the Patent Examination Guidelines through Ordinance No.68 in response to the growing need for GUI protection. Under Ordinance No. 68, a product incorporating GUIs is patentable, i f the GUIs ( i ) are relevant to human-machine interaction and (ii) ensure product functionality. Ordinance No. 68 further gives some examples of what will not meet the requirements of human machine interaction or product functionality: game interfaces, electronic screen wallpaper, boot screen and shutdown screen patterns, and website/webpage layout.

With the implementation of Ordinance No. 68, the CNIPA started accepting design patent applications for products incorporating either static or dynamic (animated) GUIs.

2. GUI design patent filing statistics

The Patent Information Service Platform of CNIPR (http://search.cnipr.com) reveals that the CNIPA received 1,027 design patent applications with a title containing the Chinese characters equivalent to “graphical user interfaces” on 1 May 2014 alone.

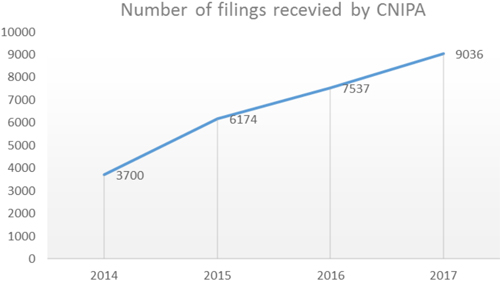

The chart below shows that the number of design patent applications incorporating GUIs grew rapidly during 2014-2017 representing a rising demand for GUI protection. [Note: The data set for 2018 was incomplete at the time of writing.]

More than half of the design patents incorporating GUIs have been issued with a title containing the Chinese characters equivalent to “graphical user interfaces” in combination with the Chinese characters equivalent to “mobile phone”, “computer”, “tablet”, or “mobile device”. Moreover, a large proportion of the applicants are software companies or online service providers who do not actually manufacture any hardware products like phones or computers.

3. China’s first GUI design patent infringement case

The plaintiffs Qihoo 3 6 0 Technology Co., Ltd. and Qizhi Software (Beijing) Co., Ltd. sued the defendant Beijing Jiangmin New Technology Co., Ltd. for infringing their design patent ZL201430329167. 3 entitled “Computer incorporating GUIs”, and requested (i) an injunction, (ii) an elimination of ill effects, and (iii) damages of 5 million Yuan.

The Beijing IP Court docketed the case on 3 May 2016, heard it on 21 September 2016, and issued a long-anticipated decision [Case No: (2016) Jing 73 Civil Preliminary No. 276] on 25 December 2017 dismissing the plaintiffs’ case.

On a related note, in retaliation for this patent infringement lawsuit, the defendant filed a patent invalidation petition against the design patent at issue with the Patent Reexamination Board (PRB) of CNIPA. On 8 March 2018, the PRB issued the Invalidation Examination Decision No. 35179 in which the design patent was held to be invalid.

1) Direct infringement

In its decision[Case No: (2016) Jing 73 Civil Preliminary No. 276], the Beijing IP Court used a two factor test to determine the scope of protection of a design patent:

Determination of the scope of protection of a design patent depends on two factors: (i) product; and (ii) design. Both factors should be identified by what is shown in the drawings or photographs of an issued patent. In this case, the product shown in the drawings is a computer, and the title of the design patent at issue is “computer incorporating GUIs”. As such, the design patent at issue should be limited to the design of computer products, and the word “computer” should be able to define the scope of protection of the design patent at issue.

Because of this two-factor test, direct design patent infringement was not found in this case for the simple reason that computer and software are different categories of products. Software to create GUI interface cannot meet the design patent requirement for the presence of a computer. Perhaps regrettably, this case was over almost before it had begun, and the Court did not need to decide how similarity of designs incorporating GUIs should be determined.

2) Contributory infringement

The Court also held that contributory infringement of the design patent has not been established.

In 2016, a patent infringement judicial interpretation from the China Supreme Court provided that one should be liable as a contributory infringer if that person knowingly provides a component especially made or adapted for use in the exploitation of a patent for someone who directly infringes the patent. [Note: It is inferred here that such component is not a staple article of commerce suitable for substantial non-infringing use.]

The Court took the view that a defendant cannot be liable for contributory infringement without an underlying direct infringement by users who directly exploit the design patent at issue, i.e. make, offer for sale, sell or import products incorporating the patented design for production or business purposes. In this case, users merely download the defendant’s software to their computers rather than making, offering for sale or selling computers. While the plaintiffs claimed that there was a possibility that users offer for sale or sell computers pre-installed with the accused software, they failed to produce evidence in support of their claims.

4. What this first case implies?

This decision has created a difficult situation for owners of GUI design patents in China and will probably discourage future applications being filed. The result will be disappointing for those from the software industry who have a strong incentive to protect their software products from being copied or imitated.

1) Figuring out who your ideal defendant is

Wining a patent infringement case is always difficult but, as a first step, you do need to figure out who your ideal defendant is.

According to the Court, if there is no direct infringement established, a defendant cannot have contributed to the infringement of a patent.

Consequently , successful enforcement of a GUI design patent needs to depend on two factors: (i) whether software can be considered a special-purpose “component”; (ii) whether there is an underlying making, offer for sale, sale or import of the hardware ( i.e. computers, phones) incorporating GUIs.

While the Beijing IP Court did not comment on the first factor in its decision, it is reasonable to assume that software to create a GUI interface could be seen to be a special-purpose “component” for use in the exploitation of a design patent directed to a computer that includes a GUI interface.

The second factor is the key to who the ideal defendant is: anyone who makes, offers for sale, sells or imports the hardware incorporating GUIs. This points to the following parties:

a) Manufacturers: If a computer manufacturer pre-installs the software on its products, then the computer manufacturer can be a direct infringer and the software developer be a contributory infringer.

b) Resellers/distributors: If a reseller/distributor sells computers pre-installed with the software, then the reseller/distributor can be a direct infringer and the software developer be a contributory infringer.

c) Importers: If an importer brings computers pre-installed with the software into China, then the importer can be a direct infringer and the software developer be a contributory infringer.

By establishing that one or more of such parties directly infringed the design patent, the software developer may then be held to be a contributory infringer or possibly a party to the direct infringement. If the target is actually the software developer, it will be necessary to go through a direct infringer to hit that target

2) Lack of partial design protection

The problem this decision highlights is the lack of partial design protection under the China Patent Law, which remains unchanged since its third amendment in 2008. Section 7.4, Chapter 3, Part 1 of the Patent Examination Guide lines rules out partial design protection by providing that any component part of products which cannot be separated or sold and used independently (such as the heel of socks, the peak of a hat, the handle of a cup) is ineligible for design patent protection.

Partial design protection is available in the U.S., Japan, South Korea and the European Union. The Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) issued by the USPTO, for instance, establishes partial design protection system in the U.S. The USPTO states in Section 1502, Chapter 1500 of the MPEP that in a design patent application, the subject matter which is claimed is the design embodied in or applied to an article of manufacture (or portion thereof) and not the article itself.

In the final analysis, a GUI is something like a virtual control panel that enables users to operate a product. Since a GUI is inseparable from the product to which it is applied and cannot exist alone merely as surface ornamentation, a GUI per se is not patentable in China and it must be embodied in the screen of a product. When filing design patent applications, an applicant needs to illustrate in an application a physical product incorporating GUIs, and to name the design patent application “[device] incorporating GUIs”.

In jurisdictions (e.g. the U.S.) where partial design protection is available, structure that is not part of the claimed design, but is considered necessary to illustrate the environment in which the design is associated or the article embodying the design is used, may be represented in drawings by broken lines. For GUI design patents, this means that the physical product is no longer a consideration when determining the scope of protection. In contrast, in China products must be shown in solid lines and broken lines are not allowed.

There are encouraging signs, however, that the attitude to partial design protection in China is changing. Partial design protection is now among the most discussed topics on the proposed fourth amendment to the China Patent Law, as it is becoming increasingly essential for industrial sectors that are technically mature and thus the degree of freedom of designers in creating something original and/or different is not wide.

3) Enforcement difficulty

In line with the Court decision, the design of the physical product that in corporates GUIs is a consideration in assessing the scope of protection of a design patent. More importantly, the Court made it very clear that even though the GUI designs of the alleged infringing software are identical or similar to the GUI designs covered by the design patent at issue, the alleged infringing software does not fall within the scope of protection of the design patent at issue.

Unfortunately, China’s current patent system seems to be unable to provide protection for GUI designs sufficiently wide for enforcement purposes, since others can easily circumvent an issued design patent by using the same GUI designs but on a different product.

4) Current rules remain applicable

As noted by the Court, there are no specific rules of determining GUI design patent infringement in China. As such, the current generally applied rules as outlined below still apply.

Design patent infringement occurs when the accused design of a product does not produce a different overall visual effect on the informed user from that produced by the patented design of the product of the same or similar category.

Courts in China normally carry out the two-factor test to determine the scope of protection of a design patent. While the first factor (i.e. whether the products of both parties belong to the same or similar category) is something objective and straight forward, the second one (i.e. whether the designs of both parties are similar) is more subjective but can be determined by the following procedure:

a) Breaking down the patented design and the alleged infringing design into features, and excluding features dictated solely by function;

b) Creating a list of similarities and differences after one-by-one comparison of all the features of the visible parts of the patented design and the alleged infringing design;

c) Considering each similarity and difference from the design freedom point of view and against the design corpus in order to give it appropriate weight or significance;

d) Deciding whether the alleged infringing design produces on the informed user a different overall visual effect, taking into consideration all the similarities and differences appropriately weighted.

It is worth noting that in April 2017 the Beijing Higher Court issued the Guidelines for Patent Infringement Determination (2017). These Guidelines require that courts primarily consider the GUI part of a product while taking into account the positional , proportional , dimensional and distribution relationships of the GUI part and the rest part of the product. It further provides that when the non-GUI part (e.g. a physical product that incorporates the GUIs) embodies a usual design, the GUI part has more significant influence on the overall visual effect.

5) Copyright approach, an effective alternative or dead-end?

As a GUI is part of computer software, GUI design owners may naturally resort to copyright system for protection. Regrettably, the copyright system has proved ineffective in providing effective protection in China.

Copyright protection of GUIs was first dealt with in China in a 2005 decision of the Shanghai Higher Court, Beijing Jiuqi Software Co., Ltd. v. Shanghai Tianchen Computer Software Co., Ltd.[Case No. (2005) SH Higher Civil Third (IP) Final No. 38]. Since then, copyright protection of GUIs has been denied by courts for the following reasons:

1) It is a generally accepted principle that copyright protection extends only to original expressions and not to ideas, procedures, methods of operation or mathematical concepts;

2) The individual elements of a GUI (e.g. icons, menu) are either generic designs in the public domain which are insufficiently original and/or creative to qualify for copyright protection, or merely illustrate functions, and in the aggregate, are methods of operation;

3)The whole of a GUI is often a simple combination of these individual elements and is less likely to be original or creative as well.

6) Patent approach still the best solution

Due to the inherent limitation of copyright system, the patent system may provide the best solution for GUI protection even though at present it is not perfect. Legislative change will be needed for this.

For now, it is advisable to make full use of the current design patent system to achieve the widest possible scope of protection. Here are some practical tips:

1 )When illustrating in an application a physical product to which the GUI is applied, you may use the usual design of that product to ensure that the GUI part stands out from the non-GUI part (i.e. the physical product) and is given greater weight in determining its influence on the overall visual effect. Further, you may state in the brief explanation of the design that the essential features of the design lie in the GUI part and the non-GUI part incorporates usual design.

2)If you have one GUI design that can potentially be applied to different products (e.g. a desktop computer, a tablet and a mobile phone), you may file separate applications for these products embodying the same GUI design.

3)If you have several GUI designs that can be applied to a product, be careful about your decision to file them as dynamic GUIs where each of these GUI designs is treated as a key frame or transitional image.

The downside of pursuing a design patent for dynamic GUIs is that you will be left with a relatively narrow scope of protection that is defined by a combination of animated transitions illustrated by all the key frames. Suggestions are:

a) If you wish to protect each of these GUI designs but not the animated transitions, you can file them as static GUIs either in one multiple design application (if these GUI designs are similar and the number of them is no more than ten) or in separate applications (if these GUI designs are dissimilar);

b) If you wish to protect each of these GUI designs as well as the animated transitions, then you may consider filing them as dynamic GUIs.

4)When considering taking action for infringement of a GUI design patent, make sure that at least one defendant is a direct infringer of the patent.