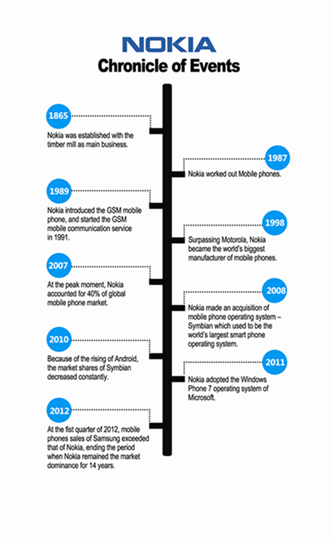

Nokia’s go-it-alone strategy is proved to be a flop. It abandoned Symbian and Meego, rejected Android, allied with Microsoft, betted on Windows Phone and resulted in plunge of its share prices, massive layoffs, management overhaul, sale of its headquarter office building and closure of its factories. It has been a synonym for low-priced phones. Nokia, with 147 years of history and 14 years of glorious dominance in the global telecommunications industry, has nowadays fallen into oblivion suddenly.

What is behind the fall? It is, certainly, Steve Jobs and his iPhone. In 2007 when Apple launched iPhone, Nokia did not fail to sniff out potentials in the smart phone market: its initiatives and measures showed that it had shifted its focus to smart phones. In January 2008, Nokia acquired Trolltech, the Norwegian developer of Qt, the cross-platform application development framework used for the development of GUI programs. According to reports, at that time Nokia owned Maemo and Symbian operating systems as well as the Qt development framework. Unfortunately, the internal politics and conflicts between the Symbian and Linux teams resulted in a compromise porting Qt on the Symbian. Later, Android began to flex its muscles and Symbian aged quickly. Maemo and Mobile merged to form Meego with Qt as its core framework. Nokia’s CEO Stephen Elop, a former head of Microsoft business division, unveiled a new strategic alliance with Microsoft, and announced it would shift its efforts to Windows Phone from Linux-based Meego and Symbian except for nonsmart phones. However, the alliance and shift increased slim chances of Nokia making a come-back due to the changing market where the top-end iOS and open-sourced Android had captured 82% of the market. In the first quarter of 2012, Samsung outsold Nokia in terms of mobile phones, terminating the 14-year glory of Nokia.

New Nokia’s transformation a certainty

In September 2013, Microsoft announced that it would acquire Nokia’s mobile device business in a deal worth 3.79 billion euros, along with another 1.65 billion euros to license Nokia’s portfolio of patents for 10 years; a deal totaling at over 5.4 billion euros (7.17 billion US dollars) all paid in cash. Nokia estimated that the deal would help it gain 3.2 billion euros in profits. In 2012, the mobile device business which Nokia planned to sell had earned it 14.9 billion euros, accounting for 50% of the total revenue. As part of the deal, Nokia would grant 10-year non-inclusive licence of its patents to Microsoft while Microsoft would provide Nokia with patent licences relating to mapping services.

Under the deal, Microsoft had right to extend the patent cooperation. Microsoft would also be granted access to Nokia’s Here platform and become the largest client of Nokia. The licensing fees would be paid under a separate licence agreement.

The move has caused concerns that Nokia may turn into a non-practicing entity (NPE). According to JP Morgan’s statistics, the number of Nokia’s patent portfolio hit 30,000, but currently only 10% of them have been licensed. In other words, about 90% of new Nokia’s patents have not been licensed, which may relate to the fact that Nokia’s mobile device business has not been acquired by Microsoft before.

A recent news report also brought back anxieties over Nokia’s transformation. According to South Korean media, Nokia has recently demanded high patent royalties from Samsung Electronics and LG Electronics, and negotiations through arbitration are ongoing in the U.S. It is reported that Nokia has taken the patent offensive since the sale of its mobile device business to Microsoft. Under the deal with Microsoft, Nokia may exercise the relevant patent rights even if it does not engage in the manufacturing of mobile phones. Some held that Nokia is most likely to become a NPE. In general, mobile phone manufacturers often reduce patent expenses by cross-licensing; however, Nokia now gets out of the manufacturing, and may demand royalties from other manufacturers. Most of Nokia’s patents are standard essential ones which make it difficult for others to bypass. Therefore, South School of Intellectual Property in Shanghai University, Professor Yuan said, “Whether Nokia is a NPE or not depends on the definition of NPE. It is generally understood that the NPE is a polite way of addressing a company which generates its revenue from its patents, and it is called a ‘patent troll’ Korean manufacturers wish to minimize the expenses through negotiations.

It may have been a speculation over Nokia ’s possible transformation into a NPE last year, but the recent demand by Nokia for high royalty sumsies from Samsung and LG has confirmed its intention to turn into a NPE. Firstly, Nokia sold its mobile device business to Microsoft, but kept the device related patents, the structuring of the deal has paved the way for the reliance of Nokia on the patents for future revenue. Secondly, the patent maintenance fees and costs are high, particularly for Nokia with tens of thousands of patents. Its royalties may compensate the patent holders in maintenance fees and previous R & D investments. Thirdly, Nokia has got out of the phone manufacturing business, if it cannot make profits by means of patent licensing or litigation, it will make no sense to its continued holding of the patents. Therefore, Nokia’s transformation is entirely predictable.

However, in an interview by China IP, with Yuan Zhenfu, Associate President of School of Intellectual Property in Shanghai University, Professor Yuan said, “Whether Nokia is a NPE or not depends on the definition of NPE. It is generally understood that the NPE is a polite way of addressing a company which generates its revenue from its patents, and it is called a ‘patent troll’ in a sharp or derogatory way. If the NPE is limited to a company which does not manufacture any products or provide any technical services, but only relies on obtaining patents to make profits (through litigation in particular), then Nokia cannot be called a NPE in the strict sense so long as it provides other products or services, to say nothing of a ‘patent troll’.”

Patent pressure from Nokia

In terms of the manufacturers licensed by Nokia, the vast bulk of Nokia’s profits come from Apple and Samsung, followed by Motorola, HTC, Blackberry, LG, Sony and the international mobile phone manufacturers using Google’s Android operating sys tem. However, slack sales of Motorola, HTC, Blackberry, LG and Sony in the smart phone market will certainly reduce Nokia’s patent licensing revenue. Compared with those fading international brands, Chinese mobile phone manufacturers are emerging, with remarkable hike in phone sales at least. Most of the phones are based on Google’s Android operating system, which will certainly encourage Nokia to ratchet up its efforts to charge licensing fees from Chinese manufacturers. According to Bernstein Research, Nokia can sign contracts with Chinese vendors that account for 14% of the global smart phone industry. This opportunity represents about 50 million euros in licensing revenues.

For some internationally renowned mobile phone manufacturers, only some patented technologies in their products are held by themselves. Generally, two or more manufacturers grant a license to each other for the exploitation of the subject-matter claimed in one or more of the patents each owns, developing a very clever and intricate relationship with mutual exploitation and mutual containment. In so doing, patent litigation and price wars will not run out of control. However, Nokia will probably change this situation.

According to reports, the average price of smart phones made by Chinese manufacturers is around 1 million US dollars. Take leading Chinese mobile phone makers Huawei, Lenovo, TCL and ZTE, all Android-based, for example, in the third quarter of 2013, the average selling price hited only 103.25 US dollars, and the average profit margin is 1.70%. Currently, Microsoft has charged patent royal ties from Android-based smart phone manufacturers, at about 5 US dollars (5% of the cost price) for each smart phone, and 10 US dollars for each tablet PC. In the meanwhile, the price of smart phones has been going down due to increasing competition and the rise of low-end smart phones. According to statistics from International Data Corporation (IDC), the average price of smart phones will continue to fall at about 7% over the next five years.

What impact will Nokia’s transformation have on the related industries? Professor Yuan said that the following factors should be considered: firstly, the areas and product lines of the distribution of Nokia’s patents. If Nokia’s patents mainly relate to Android manufacturers, they will face relatively great pressure. The second factor is the number and proportion of essential standard patents in the overall patent portfolio of Nokia. If the patents are those that cannot be bypassed by manufacturers, they will face greater patent pressure. The third factor concerns the attitude of Nokia in patent licensing. If Nokia is inclined to resort to litigation or take other strong measures in case of failure in negotiations, the manufacturers will face more pressure.

After Microsoft’s acquisition of Nokia, Chinese mobile phone companies are facing a life-or-death pressure. If Microsoft or Nokia increases the patent licensing fees, it will push Chinese manufacturers, which have narrow profit margins, into a more difficult situation. Ultimately, they will have to choose to exit the market or shift the cost rise to smart phone consumers.

In the opinion of Yuan, in consideration of the fact that Nokia also holds a large number of Chinese patents, and many Chinese companies have expanded their business to other countries, including particularly areas where Nokia holds patents, Chinese companies may have to pay more to Nokia in patent royalties if Nokia turns into a NPE. It has been a great concern for Chinese companies to secure relatively fair and reasonable royalties. The success of Huawei against IDC can be referred in practice.

To some extent, it can be understood that Nokia has decided to transform from a manufacturer to a technical service provider, the similar approach already taken by many other enterprises before. For example, IBM has successfully turned itself into the world’s largest computer services provider after sale of its PC business to Lenovo, and topped the annual list of U.S. patent recipients for recorded 21 consecutive years when it had earned more than 1 billion US dollars in patent royalties each year. Ericsson, a former mobile phone giant, is also now transforming into a technology services provider, getting paid enormously in royalties from many of the world telecommunications vendors, including Chinese ones. Professor Yuan stressed that “in other words, many U.S. technology companies have abandoned hardware and turned into service providers and achieved great success. Chinese vendors which mainly engage in hardware making may consider and get inspiration from this approach.”

(Translated by Wang Hongjun)

|

Copyright © 2003-2018 China Intellectual Property Magazine,All rights Reserved . www.chinaipmagazine.com 京ICP备09051062号 |

|

|